At FieldLab, we look forward to the start of each new season. We appreciate initial discussions about new projects, we like to learn about new challenges and opportunities, and we’re always excited to begin planning and preparation for new research—in the office and across the farm.

This year, before the new things begin in earnest, we thought it would be interesting to look back at a few of the highlights from 2021 that contributed to one of our best seasons to date. In all of this, we maintain a deep and abiding gratitude for all of our clients and the work that we’ve been trusted to perform. Sincerely, from all of us at FieldLab: thank you for your partnership and the opportunity to do this work that we love.

Our research typically falls into one of two categories. The first category includes trials that we place in a crop with known disease pressure, or relatively predictable pest incidence. The second relies more heavily on the effects of weather during critical growth stages. Early rain during almond bloom proliferates blossom brown rot. Warm July nights and scalding hot days help our mite populations to thrive. Spring rains germinate an even stand of weeds for our herbicide studies. With a variety of climactic factors and local pest behavior in play, much of the value we offer at FieldLab has to do with our knowledge of the outdoor laboratory. Each row, block, and crop is monitored throughout the seasons to ensure that your trials are initiated in the best place at the right time.

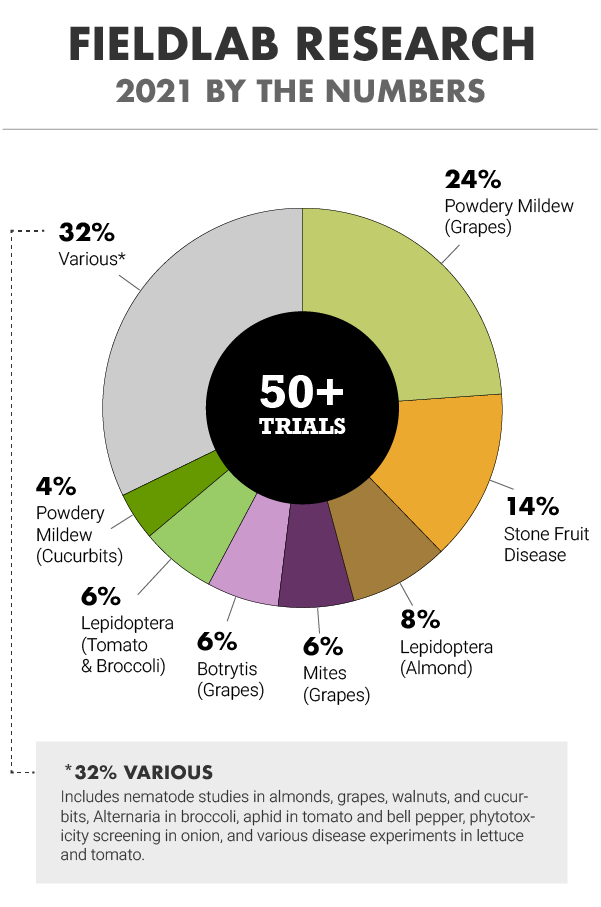

In 2021 we received a wide range of trial protocols, and we were glad to see the experiments spread out nicely throughout the season.

24% of our total trial load was dedicated to powdery mildew in grape (Uncinula Necator): these trials were initiated by May 5th, and concluded by September 15th. Disease pressure in the UTC was observed to be roughly 7% by June 15th, 33% by August 5th, and 75% by the conclusion of the trials. Despite feedback from our clients that this was a slower year for the pathogen, we experienced research-grade pressure in both Chardonnay and Carignane varieties. In total, we generated 84,120 data points, closely split between leaves and clusters throughout the season as the disease progressed.

14% of our trial load was dedicated to blossom brown rot (Monilinia Laxa) in stone fruit. All of these trials were initiated by February 20th, according to crop stages as prescribed in the respective protocol schedules. The subsequent dry spring, punctuated by an abundance of cold and windy days produced little evidence of the disease in its early infection stages. Most clients confirmed this trend across the state, so there was some consolation in the fact that our conditions in Hickman were not particularly anomalous. Out of these trials we were able to salvage some data on monilinia by adding sequential late season applications and conducting storage evaluations for brown rot. This portion of the research was successful, and it underscores the fact that we do indeed have the pathogen in our field, if only the rain and sun will cooperate.

2021 ended in fine fashion with every trial concluding by the start of November, and no crops damaged by early frost. We’re thankful for that. Over the past 11 years we’ve learned to plant fall crops in a way that optimizes the potential for pest pressure, while ensuring our best chance of seeing the crop through to the very end.

Our goal each year is to engage the work that we know we can execute with the highest confidence and probability for producing meaningful data. We continue to operate on an essential combination of in-field experience, untethered curiosity, excessive caffeine consumption, and sturdy determination to face each day fully dedicated to doing what we do best. Apply, observe, report. This is how we grow.